When it comes to election technologies, the black box phenomenon creates serious problems with public trust and confidence. The good news is that the history of election technology usage has already given us some practical solutions to these problems.

Where the best practices are not followed, however, everything hinges on the faith that this is the right piece of technology for the job, and that it will all work out fine on election day. One of those cases was Nigeria and its Bimodal Voter Accreditation System (BVAS), deployed during the series of elections earlier in 2023, which I was able to observe as part of an international observation mission on the ground for slightly more than two months.

What was the idea behind BVAS – and what went wrong?

BVAS: Improving the integrity of elections

A brief Google or YouTube search for Nigerian elections is enough to give you the idea that the electoral process in the country has not always been fair, accountable and transparent in the past. You’ll find testimonies and even smartphone footage from election days showing ballot stuffing, or criminal gangs snatching ballot boxes and replacing the contents with pre-marked ballots in favour of their preferred candidates.

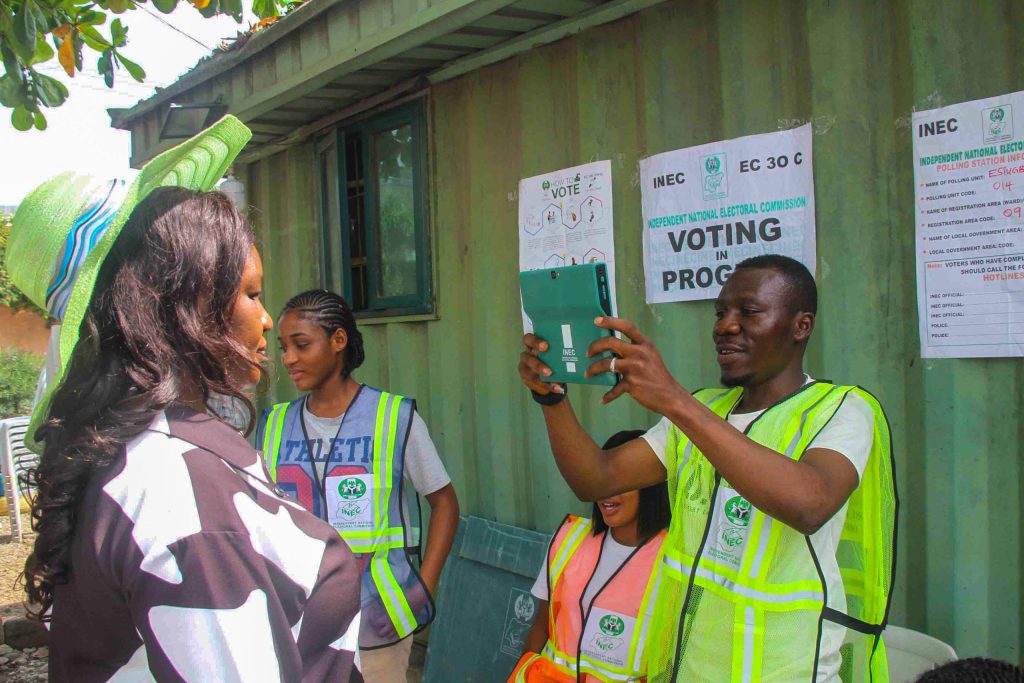

It is against this background that BVAS was introduced. The device combines two biometric technologies – fingerprint and facial recognition – to verify and authenticate voters during elections.

Its second role was to scan the election day results sheets and upload them onto a state-managed online platform. It was hoped that during the elections in 2023, this small tablet-like device would make attempts at multiple voting (ballot stuffing) impossible, as well as making the election process as a whole more transparent, accountable and fair, resulting in significantly improved election integrity.

Hopes of fairer elections

The appearance of BVAS saw many Nigerians pin their hopes on this new piece of election technology. Not only did they hope for fairer elections. They also hoped it would play a role in establishing a new political class, in turn reshaping the country’s future.

In other words: The level of trust and hope pinned to BVAS before the elections was tremendous. There was a general sense that ‘BVAS will work perfectly on the election day,’ although no citizen or expert groups were active in explaining the functionalities of the system. This trust in BVAS was so widely accepted that it ended up concealing several problems with its implementation.

The authorities and the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) missed a crucial opportunity to conduct a genuine election simulation using BVAS. Although a nationwide exercise was organised, several elements were missing, thus denying stakeholders the chance to validate the system’s reliability and efficiency in real-world conditions.

The trust in the whole system was so high in the INEC that they even decided not to use the option to secure the internet connection, needed for the uploading of the results, with an additional data card from a second mobile operator.

Technical problems on the day

On the day of the presidential election, 25 February, the whole system supporting the functionalities of BVAS failed in several respects.

The polling units opened very late, significantly decreasing the time available for voting. In this situation, the use of BVAS caused additional delay in the voting and accreditation process, as the simple act of putting fingerprints and taking facial recognition takes much longer than simply writing a signature. The fingerprint module of the device had a very high rejection rate, and ultimately, most of the voters had to be accredited through the use of facial recognition.

At the end of election day, when polling units had to scan and upload the results sheets and to reconcile the numbers of voters in BVAS and the ballots before the eyes of party agents, everything collapsed. In some locations, the problem was the internet connection. At others, it was the lack of technical knowledge among the polling unit staff. Most frequently of all, it was a problem with the INEC platform where the sheets had to be uploaded.

As a result, none of the safeguards that were initially planned to ensure the fairness and the transparency of the tabulation of the results were functional. The numbers of accredited voters, which had to be sent automatically to INEC and be made public on the web platform, could only be transmitted several hours late. Polling unit staff were seen uploading their sheets in the tallying centres, without the presence of any party agents, almost 24 hours after the end of the Election day.

The result was widespread discontent among many political parties and candidates, and even higher levels of distrust from the media and the society.

Lessons learned on implementing election technologies

Why did the technology fail? Was it a purely technological problem, or a case of bad implementation?

Most of the issues which occurred during those elections could have been foreseen and prevented. A number of cases in the implementation of election technologies have already highlighted the need for comprehensive feasibility studies before the actual implementation.

Such studies achieve several things. They delineate the precise problems that technology aims to solve; evaluate if the chosen piece of technology can actually fulfil its intended role; evaluate the suitability and practicality of the chosen technology; and assess the capacity of the system to operate effectively in the concrete environment.

None of these criteria were met in Nigeria. One example for the lack of prior analysis in the BVAS implementation was the absence of a thorough evaluation of the network of IT specialists, and of a proper check of the stability of the mobile network needed for uploading results sheets at the end of the election day. All of this could have been analysed even before the implementation started.

Another serious problem was the lack of a full understanding of the idea of contingency plans and procedures. As elections are a very serious public exercise, and highly inclusive in nature, they require a very high level of reliability on the part of the technology. The limited time available for voting heightens the urgency of this reliability. It means that in case of failure, the reaction time for a return to business needs to be very short. In Nigeria, there were draft contingency procedures – however, in most locations, they were simply overlooked. Those procedures were not properly explained in the training materials for the technical staff, and were not part of the training.

A need for transparency going forward

One of the most significant concerns arising from the BVAS implementation was the lack of transparency. In the realm of election technologies, transparency is paramount. It builds confidence among the electorate and all the stakeholders like political parties and candidates, assuring them that although they do not see the manual process, the black box of technology is doing the job correctly. You cannot replace the factual proof that the system works as expected with pure faith or hope.

It is quite common for election authorities to underestimate the importance of initial analysis, testing and auditing, as well as the planning processes when implementing technologies. Many of those elements are lacking, while others are done pro-forma, for the sake of formality and missing the main point.

However, without a properly planned implementation, even well-chosen election technology can fail, and even end up increasing the deficiencies in the election process. More transparency, setting up clear measures and practices for the support of the technological processes and investing even more in training are crucial if systems like BVAS are to work.

Since INEC is currently organising off-cycle elections in the states of Imo, Kogi and Bayelsa, Nigeria still has the opportunity to improve the process and outcome and make BVAS into a success story.