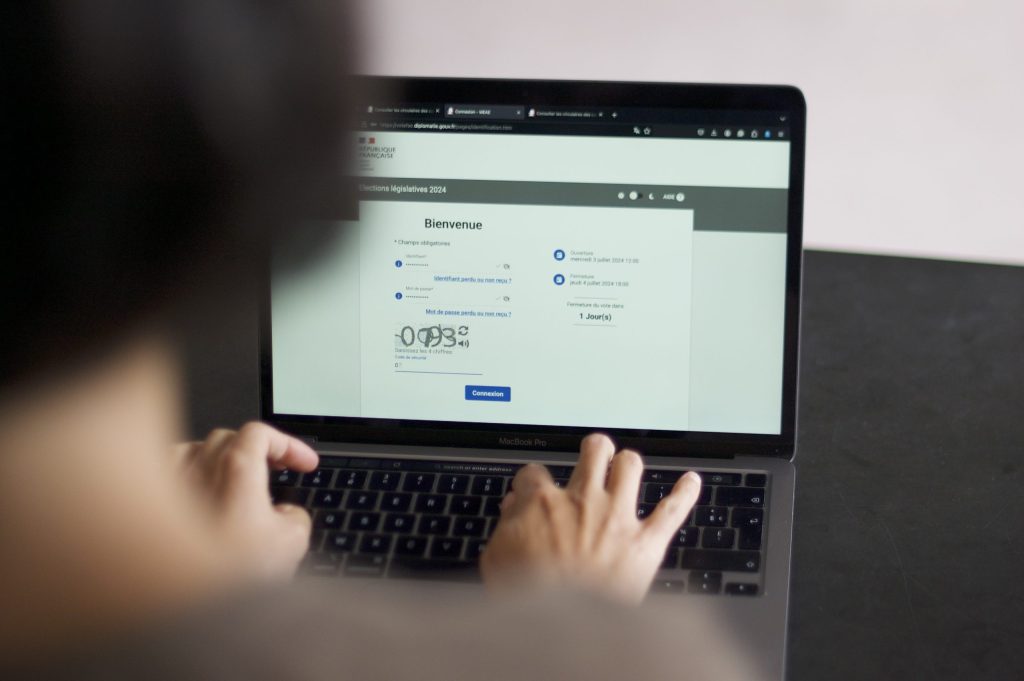

Voters in France will head to the polls this Sunday for the second round of the legislative elections. But hundreds of thousands of French citizens living abroad are already casting their votes online. In last week’s first round, over 410,000 votes were cast using the e-voting system developed by French company Voxaly. It’s a new record for France, and one of the biggest online parliamentary elections ever to have taken place.

French citizens living abroad can be seen as an individual voting block. They have their own representatives in parliament, electing 11 of a total of 577 seats in France’s parliament. In 2017, 10 of the 11 seats went to Macron’s party En marche. In the first round of the legislative elections last week, Macron’s Ensemble party came out on top in just five territories. The leftwing New Popular Front won in five regions, and the conservative Republicans in one.

Turnout among French voters abroad has historically been low. The abstention rate in the 2017 legislative elections, when online voting was made unavailable, reached 84%. The reintroduction of online voting in 2022 corresponded with a modest fall in abstention to 76%. The exact numbers for the 2024 election have not yet been reported. While the initial numbers suggest a strong showing, this is likely to be the concern of voters abroad over the rise of the far right, and is not necessarily linked to the availability of online voting.

Availability of online voting limited

At the moment, only French citizens living abroad can vote online, and only in certain elections. The reason for this is simple. “State-of-the-art online voting does not offer the same security level as on-site paper voting, as it is organised in France,” explains Véronique Cortier.

Cortier is the Director of Research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. A specialist in cryptography and electronic voting, she was part of an independent team of academics contracted by the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs to provide third-party verification for the 2022 legislative elections.

While online voting is not as safe as traditional paper ballots, practical concerns make it a strong option for overseas voters. “A compromise has to be made between the best security level and allowing a large number of voters to vote,” says Cortier. “This is why online voting is allowed for French citizens living abroad, for legislative elections. On the other hand, it is not possible to vote online for presidential elections, because the stakes are considered too high.” Likewise, French voters in the EU elections in June were not able to vote online.

Online voting preferred over postal voting

French residents abroad usually have four options to vote from abroad in legislative elections. They can vote in person at one of the many polling stations set up in overseas territories at embassies or other public buildings. They can vote by proxy, designating another person to vote on their behalf. Alternatively, they can vote by post, or finally online.

This year, postal voting was not available, possibly due to the short amount of time available to arrange the election. (The first round of voting took place just three weeks after Macron called the election on 9 June). Yet it is also notable that in the last 2022 elections, just 0.4% of French people living abroad submitted a postal vote. Furthermore, the website of the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs actively discourages voters from applying for a postal vote, citing potential delays with post.

Issues with postal votes in the UK

This is in stark contrast to a large number of countries who rely largely on postal ballots for overseas voters. In the UK’s election, held in the same week as the second round of France’s legislative elections, overseas voters have only the option of a proxy vote or a postal vote. Media reports suggest that delays in postal services have prevented some Brits from casting their vote, prompting experts to suggest it could lead to results being contested.

“Postal voting is risky, and e-voting may actually offer more security, depending on the threats,” says Cortier. While online voting tends to be subjected to very strict regulations to ensure that it is secure, Cortier argues that “the same rigorous security analysis should be conducted for any form of voting.”

In France, online voting has established itself as the most popular channel for citizens abroad, with 77% voting online in 2022. While the official numbers have not yet been published, the Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs reported on Twitter/X that over 410,000 votes were cast online in the first round, suggesting it was again the most popular option by a considerable margin.

A brief history of online voting in France

France first introduced e-voting for the legislative elections in 2012, with an e-voting system developed by Scytl, when 220,000 votes were cast online across both rounds. Online voting was dropped shortly before the 2017 legislative election due to security concerns. Yet it returned in 2022 with a new system developed by the French company Voxaly.

The new system has not been entirely problem-free. To cast their vote, voters need to submit two codes: a login code sent to them by email, and a password sent by SMS.

In early 2023, French courts overturned the results of the legislative election in 2 of the 11 overseas territories (Central and South America and the Middle East) after a large number of people did not receive one or both of these codes. The election was repeated in April 2023, and no similar issues were reported.

Ahead of e-voting opening last Wednesday, the site of France Diplomatie warned users of possible difficulties accessing the site “due to heavy demand”. As polls opened, several overseas voters took to X/Twitter to report that they were unable to access the website. Similar reports followed on Wednesday 3rd July as polling for the second round opened. In both cases, the problem eased later into the voting period.

The e-voting system

One of the key measures of online voting is verifiability. Experts often cite end-to-end user verifiability as a gold standard. It allows voters to individually ensure that their vote was recorded correctly and that it was included in the final tally.

Cortier explains that France’s online voting system achieves “individual verifiability and proxy universal verifiability.” The former means that all voters can check that their vote was included in the final tally. “Right after voting, a voter is issued a receipt that contains a signed hash of their (encrypted) ballot. The voter may then check that the signature is valid and has been emitted by the voting server. After the tally phase, the list of the hash of each received ballot is published. Hence the voter can check that their ballot is indeed present.”

While this means voters can be sure that their vote arrived, it does not fulfill the criteria of full end-to-end user verification. This would require that voters can also verify that their vote was cast as intended, meaning that they can verify who they voted for. This can be difficult to implement while observing the secrecy of the ballot.

Following the 2022 legislative elections, Cortier and her team at Loria were tasked with verifying the results. They received a list of all ballots along with cryptographic proofs that guarantee that the published result of the election corresponds to the content of the ballots. “The verifiability is only ‘by proxy’ because the ballots remain confidential hence only we could perform these checks,” she explains.

Online voting around the world

For now, France has not reported any plans to expand the availability of online voting. Estonia remains the only country in the world to offer all of its citizens the option of voting online. Yet an increasing number of governments are experimenting with making the technology available to a limited number of their citizens, or in lower stakes elections.

Earlier this month, the Philippines announced a contract with SMS Global Technologies and US-based voting company Sequent Tech to make online voting available to overseas voters for the 2025 election. The country’s election committee said they hoped to increase participation rates. Elsewhere, the Australian State of New South Wales plans to restore the right to vote online for its citizens with visual impairment by 2027. This follows their discontinuation of a similar project in 2023.