Democracy Technologies: Can you briefly explain how VOTO works?

Julius Oblong: VOTO is a voting advice application that allows citizens to compare themselves with the positions of politicians or parties in just a few minutes. That means that both [voters and parties] answer the same set of questions, and we can then say that this party or this politician is closer to you than another one. In this way, we encourage citizens to take a closer look at an election and the questions that go with it and what candidates offer. This has been confirmed in our related research: Two thirds of users state that they have now been motivated to engage more closely with the election, the candidates and their programmes. That is basically our goal.

And what is our role? We help with the implementation and have developed a technical platform that makes adapting our tool extremely simple. It is reduced to a few clicks, so to speak. You don’t have to know how to code, you can do it yourself, and we support you in the implementation and organisation, and contribute our know-how.

DT: Who do you mainly work with? Cities?

Oblong: It varies a lot, depending on the project. But yes, among others with cities. In this case, we are working with the City of Cottbus, but even more directly with the city’s Youth Forum. We also work with more independent organisations, for example with a “Stadtjugendring” (an umbrella association of a city’s youth organisations). And now increasingly also with media organisations, for example publishing groups or the Sächsische Zeitung [a regional newspaper based in Dresden]. So it can come from very different sides.

DT: Voting Advice Applications are in widespread use. Various countries have different tools – for example Wahl-O-Mat in Germany. What distinguishes VOTO from these other tools?

Oblong: The main difference is that we can also cover elections which the Wahl-O-Mat does not cover. The regional and national centres for political education (Landeszentralen für Politische Bildung and Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung), who run the Wahl-O-Mat only do it for a very small number of elections. This kind of project is quite costly and would not be feasible for a local election or a mayoral election or for 80 constituencies in a state election, where you can perhaps look at the direct candidates. And that is the gap we are entering. We don’t want to replace the state office, but we’re trying to find a way to represent candidates and to be there when a project from the state office doesn’t take place.

DT: What does the collaboration between VOTO and the organisation usually look like? How much do you support them in adapting to the respective choice?

Oblong: That is a question of resources. We try to support them as much as we can, and as much as is necessary. For example, with the project in the district of Dithmarschen, we only provided technical support setting up VOTO. Everything else – the drafting of theses, inviting the candidates and so on – was done by the partners themselves. In Cottbus, we are providing a little more support. We helped with the editing of theses as well as with the organisation and marketing materials. But if a municipality or a partner says: “You have to organise this completely, because we don’t have the capacity for it,” that’s possible too. But of course this is more resource-intensive, as we have to put our team on it for a week.

DT: Lea Brunn, what is your role in the municipality? What motivated the use of VOTO for the election of the Lord Mayor in Cottbus?

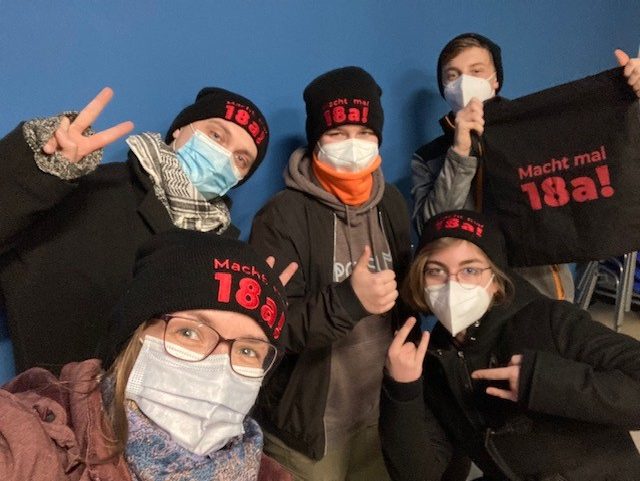

Lea Brunn: I am a children and youth representative. I work for the municipality, and my job is to implement and support paragraph 18a, so that children and young people are involved and have a say in all things that affect them. In this function I accompany the youth forum. It is not an official youth parliament, but a body of young people set up as part of the ‘Partnership for Democracy’. It has the task of deciding on funding applications for projects that are developed by young people, for young people. They do a lot of political work, and when the email from Julius Oblong came in, I discussed it with them, and they immediately thought it was a great idea, because there are so many first-time voters in Cottbus now. So it’s simply a matter of passing on information to the young people and motivating them to get to grips with what the candidates are actually about.

DT: And so the focus is on topics that interest young people?

Brunn: Yes, that’s a little bit due to my work and the fact that the youth forum said we would take this on. The theses were also created entirely by the young people. Together with the Youth Forum, we defined 11 areas, for example democracy, diversity, and leisure activities. We then contacted all those who could potentially collect theses from young people, such as schools and social workers, and asked: “Do you have theses for VOTO?” There were about 80 theses that came together, so there were a lot of them. When we did the final editing, which Julius Oblong worked a lot on it too, we only added a couple of theses ourselves. The rest all came from the young people. So it was a participatory process to arrive at these theses.

DT: Were there any sceptics when it came to setting up VOTO? In the administration or among politicians?

Brunn: Actually, yes. In the sense that as a municipality, we should of course be impartial in elections. However, our mission is simply to promote an understanding of democracy, and that is our top priority. We simply talked about it and explained that we were not going to sit down in a chamber with one of the candidates and let them choose the theses that suited them. So the concern was resolved very quickly.

DT: How did the candidates themselves react to it? How do candidates usually react?

Brunn: Almost all of them reacted positively. One candidate didn’t participate, and explained to us why he didn’t want to take part. The others were all positive.

Oblong: In our experience, the candidates and also the parties generally react quite positively to it. Especially in the context of a project that also aims to involve and motivate young people and where the process of putting together the theses is transparent. It’s quite rare for people to oppose it. However, in our experience, candidates from more extreme parties often don’t participate because they have reservations about the theses. Mostly they take offence at theses formulated in gender-inclusive language, or that are about somewhat left-wing concerns. Then they don’t want to take a position.

In other cases, there is a reluctance because various other organisations also prepare questions and send them to the candidates asking them to position themselves. Of course, that produces a lot of work. So they ask: “Is this useful? Does it reach enough people?” We also get the questions: “Where is this being disseminated? Where are these being produced?” These are the questions they are interested in.

DT: How is VOTO distributed in Cottbus? How do you make sure that the young voters take up the offer?

Brunn: I have a large network of all the organisations that are engaged in child and youth work, as well as school social workers. I distributed it to all of them and received quite positive feedback. The universities too, of course. In short, all the points where we have access to young people. But I also distributed it to everyone else in the city administration as well as the press and social media.

DT: Has the project been a success? How many people have been on the site or used it so far?

Oblong: VOTO Cottbus attracted 2,134 users, which I consider a real success. In conjunction with a mock election for under 16s held last month, it allowed two goals to be achieved at once. On the one hand, we were able to reach a large number of young people; and on the other, the candidates were made more aware of the issues important to young people. We hope that the new mayor will continue with the young people’s forum, and pursue a productive collaboration.

DT: Would you call this a form of participation?

Brunn: In a way, yes, because we got the theses from the young people, and that’s what the whole project is based on.

Oblong: The process meant that all politicians who stood for election had to deal with the issues defined by the young people and respond to them, including the next mayor. And that is of course also a form of attention that is demanded of them.