Politics nerds like me tend to love science fiction. But it doesn’t matter if you are into Star Trek or Star Wars (forgive me!). The fact is that most political professionals (even authoritarians) share an enthusiasm for a better future – and often enough, this enthusiasm is driven by technology. With the help of ever-more sophisticated technology, so the line of thought goes, we will be able to outrun our competitors in election campaigns, improve government services for all citizens, or better identify those in immediate need of help.

Similarly, citizens who have lost confidence in politicians often display a naive faith in the saving power of technology. From their perspective, since politics is failing spectacularly, technology is the only hope – for instance to save the planet.

As such, it’s no wonder that the potential applications of artificial intelligence (AI) to politics are currently inspiring a lot of dreams. And given that AI is already successfully being used to improve health care systems and to make public transport more efficient, these dreams can almost seem within reach.

But is AI up to the task of improving democracy itself? Could it be used to help bring citizens together, making possible new forms of discussion and decision-making? Our editor Daniel Mackisack took a close look at several AI tools with potential applications in deliberative processes. In the following, I consider some of the most promising avenues for exploration – and the limits already coming into view.

AI, please hold!

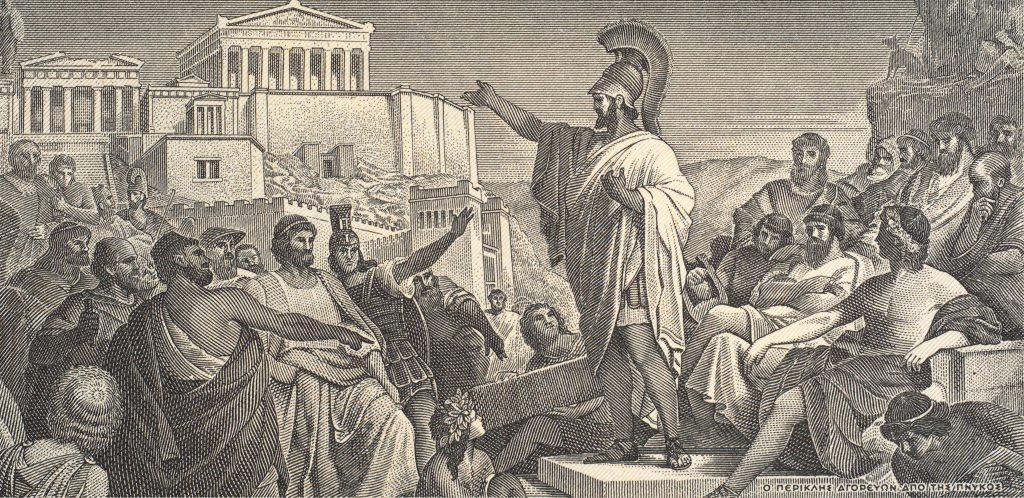

A simple example shows us how far away we are from an AI breakthrough in democracy: As trust in representative democracy is fading, political thinkers are turning their attention to participatory and deliberative democracy (“deliberation” is the boring term for something that is actually exciting – people struggling things out together instead of letting their representatives do it for them). The idea is certainly enticing: To put the will of the many at the centre of policy making, instead of the will of a handful of elected officials.

Accordingly, initiatives for citizen participation are taking root around the globe (see this list of recent projects in the UK, for example). But as these efforts are moving beyond the local level of just a handful of people gathering in meeting halls, a quantitative problem arises: The number of participating citizens is growing faster than the current methods can handle. City governments are overwhelmed with the amount of input from citizens, and lawmakers have to dig through millions of opinions.

This is where AI comes in.

Imagine for a moment that in your country, all citizens were invited to develop a plan to solve a complex issue – for example, to significantly reduce carbon emissions.

To put this into practice, you could choose between one of two main approaches, as Hélène Landemore of Yale University recently summarised:

1) Mass online deliberation. Every participant is in discussion with a gazillion others. This would undoubtedly lead to a vibrant exchange – but the result would be far too much information and social interaction for any single person to digest.

2) Small assemblies with some dozens of participants each. For millions to participate, there would have to be hundreds of thousands of such assemblies. Again, this would be rather difficult to handle. How could the results of these assemblies be complied, and how could a great thought from one assembly inspire the others?

Supporting Role

In both of the above cases, AI could be of assistance.

Some democracy technology firms, like CitizenLab, citizens.is and fluicity have been introducing promising solutions to address problems of mass participation, like translation, fact checking, sentiment analysis and clustering, distribution of content, and compiling groups online. These tools are supportive, and we can expect to see more of them.

Nonetheless, democracy is much more complex than common applications of AI, like traffic planning. With in some cases millions of arguments, it boils down to the question of relevance. Who decides which argument counts more than another? AI cannot be relied on to reach impartial decisions, as it has been shown to reproduce human biases. And so this task will fall to individuals – individuals who inevitably bring along biases of their own.

The quantitative barriers of exchange will become more obvious in the next few years. As more politicians move towards participatory and deliberative democracy, and the projects grow in scale, so more resources will flow into solving its problems.

From what we can see so far, AI will certainly have a supporting role in this play, but it won’t be a main character. And the genre is not going to be science fiction – but political drama.