Democracy Technologies: Why is participation so important in urban planning?

Sven: The tasks that a planning agency like ours undertakes for cities are so complex and touch on so many issues, that you need an integrated solution, based on cooperation. Collaborations between the public sector, the private sector, civil society and the broader public are increasingly common. We have a concrete issue to tackle, and we need to find a way of working on it together. What solutions can we find that everyone can support? What contributions can we all make?

There is also a legal dimension to participation. Cities are generally required to communicate with their residents on planning projects, to get them involved in changes to their home areas. And it’s clear that people really have a strong interest in getting involved in shaping their neighbourhoods.

DT: The city often defines the broad strokes of a project, and there are some decisions that only experts can take. How much space is left for residents to make a meaningful difference in a typical project?

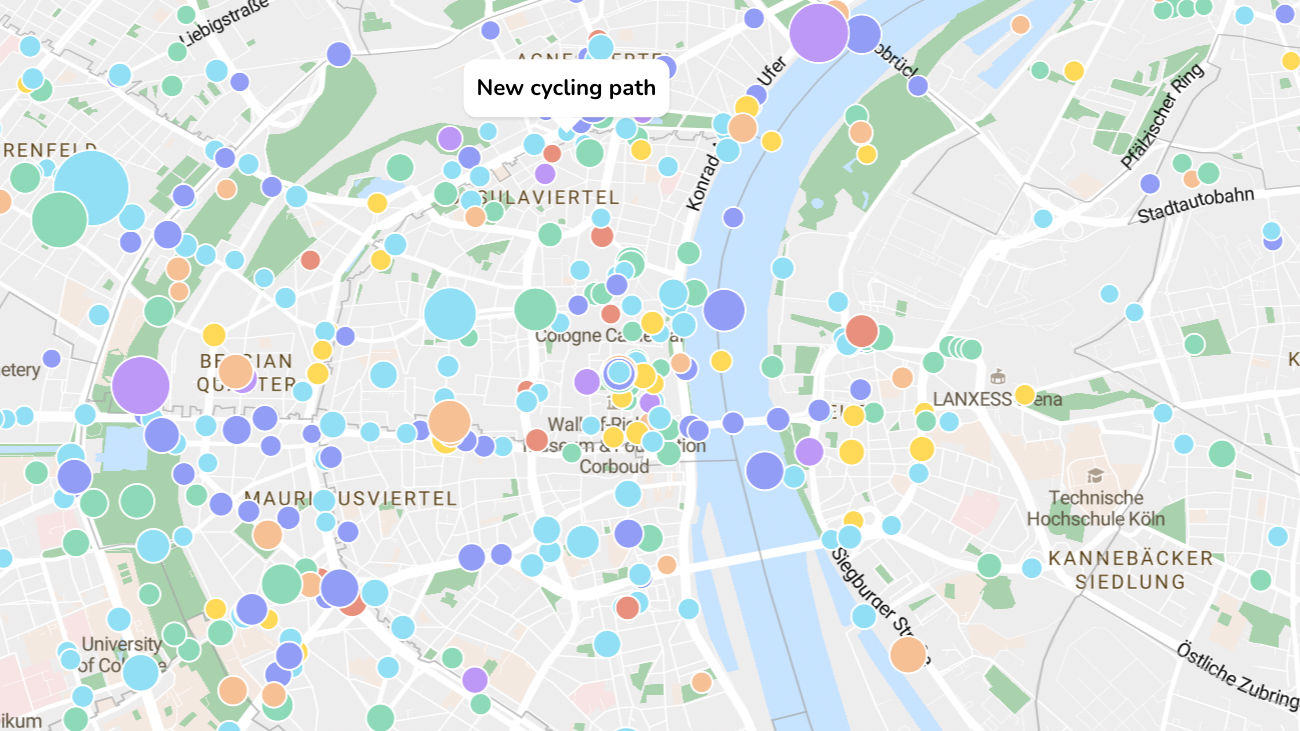

Pascal: Take the example of an urban mobility plan. On the digital participation platform, we frequently use a map-based survey. Residents might be invited to place markers on the map where they feel are dangerous spots in traffic. Often, the results are different to what accident data will tell you. So it’s an important way of gathering insights necessary to develop the project in accordance with public needs.

Sven: In my experience, participation often begins with a political decision. A city decides to launch a project and wants to have a participative aspect. But often, the goals of this participation aren’t well defined. What topics are supposed to be discussed? Which questions do you hope to get a public response to?

It’s important to define what is up for discussion, but also which topics should not be addressed in the participation process – because the decisions have already been made, or will be made elsewhere. If you don’t do this, the result is frustration or disappointment in the whole participation process. You have to ask: What are the questions that we can approach together? Where might we hope to get new ideas or suggestions? These are the first steps we need to take.

Pascal: I would add that transparency is crucial here. What is the goal of the participation? What can people hope to get out of it? If you don’t answer these questions, it only leads to frustration. If it’s not clear what happened to my inputs, I might not take part next time. So it’s also important that after a project, you communicate what will happen next.

DT: As the provider of a participation tool, what are the biggest differences between working for a city, or working for an urban planning agency?

Pascal: When we started out with Senf, we focused on city administrations and municipalities. But for several reasons, we then shifted to working with planning agencies. This helped us to understand how different stakeholders or different agencies work together with administrations, service providers, and process consultants. For us, the ideal setup in those cases is to have an administration who even before putting out their call for tenders have already thought about how they want to shape the participation process.

Generally though, when we work together with a private customer, there tends to be a lot more space for creativity in shaping the participation process than in projects with a city or a municipality.

Sven: On the other hand, municipalities sometimes have more resources for this kind of thing than private customers. In my experience, in public administrations, there are often a lot of people who take the theme of participation very, very seriously. However, being able to implement participation often has a lot to do with staff availability and financial resources. And sometimes they are just overwhelmed with other tasks they have to fulfil.

Pascal: That’s a very important point. A city like Cologne, for example, has quite a lot of resources and a great team who are capable of delivering a very wide-ranging participation project. Their mobility plan involved eight or nine events, accompanied by digital formats. These resources definitely play a big role.

DT: City planning can involve conflicts. What role do you see for participation in dealing with conflicts?

Pascal: We see participation as a way of creating acceptance. It can resolve conflicts by seeking out dialogue, and acting transparently. The recent attempt to close a street in the centre of Berlin to traffic is a good example of how these can lead to very emotional debates and polarised positions. In these cases, it is above all the critical voices that tend to be the most visible.

Sven: Pretty much any city planning project is going to involve disagreements, and the need to balance the interests of different groups. I can’t think of many projects I was involved in that didn’t involve some conflict. Some people flinch at the word conflict, but productive disagreement is one of the cornerstones of democracy. It’s not a bad thing, as long as it takes place in a regulated space. In the end, you can reach decisions which everyone is able to accept.

DT: Are these conflicts an area where digital tools for participation come up against their limits?

Pascal: Yes and no. Digital tools are a really important way of reaching people who don’t have the time for in-person formats, or people dealing with language barriers. But it isn’t always the best way to deal with conflicts. We did a traffic project in the German city of Kassel where the digital platform ended up being used as a way for people to let out their frustration. The anonymity of the process meant that people’s inhibitions were lower. We took steps to address this, including offering the option to make registration for specific projects compulsory.

Sven: I think digital and analogue are both important. I have definitely noticed that speaking to planners in person on an equal footing can really lead to an “aha!” moment. When there is a model on the table in front of you, and you can ask “why did you do it this way, and not like this?” And the architects can respond: We did try doing it your way, but it didn’t work for the following reasons. And people then usually respond “Okay, I understand.” You can’t really recreate those moments in digital spaces.

At the same time, digital tools allow you to reach completely different target groups. And they also have the capacity to really improve the whole process. AI tools could give someone who can’t draw the chance to share their ideas by assisting them in creating a plan of an urban space, just by describing it. It would give them a concrete idea of what their ideas would look like in reality.

Or a simulator which would allow me to design a city neighbourhood, and the tool would tell me “Look out, you’ve forgotten the needs of this group of residents; are you sure you really want to do it like this?” I’m convinced it’s going to take things to a whole new level.

DT: Are these tools you are working on, or are they more something you’d like to see in future of digital urban planning?

Pascal: We’re already working on the first example Sven gave, the drawing tools. These things are already possible, and it won’t be long before we can use them to allow residents to create their own visual inputs to the process. Both of us are also working on gamification. For example, we developed a tool where residents can take on the role of the mayor of a city. They are taken through several steps requiring them to allocate the budget in order to develop an urban area according to their plans.

Sven: Looking further forward into the future, I like the idea of mixed reality. I dream of an event where you have a huge map in front of you with overlaid digital elements. Participants could make their way through the map together, and different layers could be added or removed.

Pascal: I find the idea of participation via the Metaverse interesting, or using augmented reality glasses to explore a city map. There are really no limits to the ways you could use these tools to get residents more involved in city planning and to make the whole participation process more fun.